On Board Boats

Chapter 1

The Dream

The conventional

wisdom has it that only very rich people or fools buy new boats. I am not a rich person by

any of the usual measures. Nor do I consider myself a fool. But I do own a new boat, which

has me doing an inordinate amount of daydreaming on cold wintery days. And, I must admit,

I do have some anxiety about the financing of this wildly reckless extravagance. The story

of this acquisition begins a long time ago and requires the telling of a number of stories

from my childhood.

My maternal grandfather,

William McGill Burns (Admiral, USNR), grew up on Shelter Island, off the eastern tip of Long Island, New York. After a stint in college in

Philadelphia and commissions in both the Army and the Navy he did return to Shelter

Island, albeit for short stays in the summer. My mother and grandmother often talk of

spending summers in a rented house on Shelter Island. As a Naval Reserve Officer and a

native of an island with a long seafaring history it wasn't long before my grandfather

owned a boat. In fact, there were at least two. To the above right is the first Kay

Ruth. This photo was taken in 1946.

eastern tip of Long Island, New York. After a stint in college in

Philadelphia and commissions in both the Army and the Navy he did return to Shelter

Island, albeit for short stays in the summer. My mother and grandmother often talk of

spending summers in a rented house on Shelter Island. As a Naval Reserve Officer and a

native of an island with a long seafaring history it wasn't long before my grandfather

owned a boat. In fact, there were at least two. To the above right is the first Kay

Ruth. This photo was taken in 1946.

The only one of these boats

with which I was familiar was the Kay Ruth II, named after my mother and

grandmother. The Kay Ruth II is pictured at the left. My grandfather owned her

from 1952-1963. The boat was a forty foot Matthews outfitted as a sport fisher, with two

great long outriggers originating at the aft edge of the cabin and rising into the

sky. In the photo they are in front of the cabin so my grandfather must have changed

them at some point. Those outriggers gave the impression of being the antennae of a

gigantic bug. But the clear plastic rings to guide the fishing lines along their length,

and the intermittent black stripes along their white length, gave the lie to that

interpretation. She had twin inboard engines, a v-berth in the forecastle, an owner's

cabin, galley, head, and large saloon. The dining table and opposing benches could be

folded down to form a double bed. The banquette, also in the saloon, provided

accommodation for at least one more tired sailor. The hull and cabin were, of course,

wood. Fiberglass was not then an accepted construction material. The quantity of high

gloss mahogany was beyond belief. Every winter the boat was taken out of the water and

kept under cover so that all that wood could be repainted and varnished. All in all, it

was quite a boat, at least in the eyes of a boy less than ten years old.

The only one of these boats

with which I was familiar was the Kay Ruth II, named after my mother and

grandmother. The Kay Ruth II is pictured at the left. My grandfather owned her

from 1952-1963. The boat was a forty foot Matthews outfitted as a sport fisher, with two

great long outriggers originating at the aft edge of the cabin and rising into the

sky. In the photo they are in front of the cabin so my grandfather must have changed

them at some point. Those outriggers gave the impression of being the antennae of a

gigantic bug. But the clear plastic rings to guide the fishing lines along their length,

and the intermittent black stripes along their white length, gave the lie to that

interpretation. She had twin inboard engines, a v-berth in the forecastle, an owner's

cabin, galley, head, and large saloon. The dining table and opposing benches could be

folded down to form a double bed. The banquette, also in the saloon, provided

accommodation for at least one more tired sailor. The hull and cabin were, of course,

wood. Fiberglass was not then an accepted construction material. The quantity of high

gloss mahogany was beyond belief. Every winter the boat was taken out of the water and

kept under cover so that all that wood could be repainted and varnished. All in all, it

was quite a boat, at least in the eyes of a boy less than ten years old.

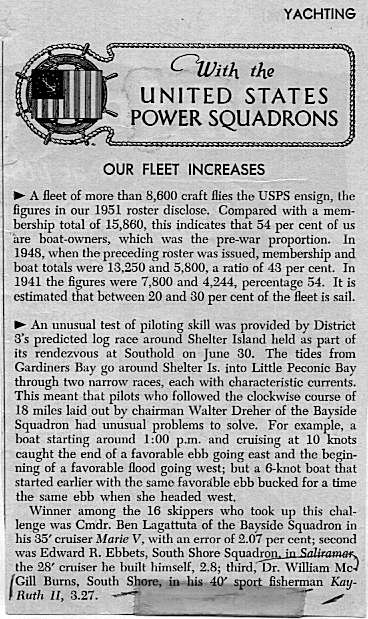

To

the left is a clipping my grandmother sent to me. It describes one of my

grandfather's voyages with Kay Ruth II. It must have been in 1952 or 1953, given the

discussion in the first paragraph and the period during which he owned the boat.

To

the left is a clipping my grandmother sent to me. It describes one of my

grandfather's voyages with Kay Ruth II. It must have been in 1952 or 1953, given the

discussion in the first paragraph and the period during which he owned the boat.

We grandchildren were

occasionally taken out to Shelter Island for short summer vacations. We would have liked

to stay longer but our parents and grandparents had a different agenda. Besides, the old

saying that a boat shrinks a foot for every day that you are on it was probably coined by

a grandfather vacationing with some of his very young progeny.

I remember a number of

events from those few trips. I suppose that most of my recollections occurred on only one

or two trips, but spreading them over several expeditions makes the memories more savory.

When you have a cabin cruiser with two great, enormous, marine-blue throbbing engines

below decks you cannot remain self respecting for very long if the boat never leaves its

mooring. And as a Rear Admiral in the Naval Reserve my grandfather was quite proud of

flying the appropriate ensign. So there you have a great deal of peer pressure to get that

boat underway once in a while. Also, it seemed to me, and probably to others as well, that

the engines required an awful lot of tinkering much to the delight of the local marine

mechanic. So it was under these circumstances that it was decided that we would make an

overnight trip to Block Island. 'Pop' got out his charts in order to plot the course we

would take. Under the guise of telling the yacht club commodore where we were going, he

checked on the operation of the ship to shore telephone. And in order to impress us with

his knowledge of state-of-the-art technology he made sure that the radio direction finder

was in working order. The charts, and checking the RDF and telephone routine were probably

unnecessary given that Pop was an inveterate tinkerer and knew the way to Block Island

from many previous trips. But then I suppose he was trying to impress upon us the

importance of preparation and routine for safety.

In any case, those

engines were brought to life. Individually they came rumbling and throbbing up from the

hold. The machismo of all that horsepower was something. It just went right to your balls.

In those days, it may still be the case, the engine exhaust was right at the waterline on

the transom, below a great expanse of high gloss mahogany with the boat's name in gold

letters. The effect of having the exhaust at the water line was that as the boat rocked

the exhaust pipes would alternately dip below the waterline. Well, the boat was already

rumbling and vibrating from the twin engines, then the water would swallow and release

with some amplification the exhaust which you just knew was going to be thunderous when we

got under way. But that only came after the engines were adequately warmed up; remember

those babies were notoriously cantankerous.

The trip to Block Island

was probably pretty mundane, even boring, for the adults on board. But for me it was

wonderful, at least at the beginning. Oh, I'd been on ferries out of sight of land before,

but this was a small boat, relatively speaking, and the captain was my grandfather. We

were told about the use of the outriggers for tuna fishing and why the chairs on the deck

at the stern had those steel tubes bolted to them. We got a demonstration of the radio

direction finder. And we were allowed to sit up on the deck in front of the wheel house.

And we sat. And we sat. I suppose Pop sensed our creeping boredom because he announced

that with the binoculars we could see Block Island. Using the binoculars kept us occupied

for at least another two minutes each. Thirty years later I don't remember too many other

details of the trip. Suffice it to say that we did get back to Shelter Island, my mother

did not put us up for adoption, and Pop did invite us back for other cruises.

I am sure that in

everyone's encounter with boating a dinghy plays a prominent role. As is so often the

case, Pop's dinghy did not have a name. That didn't seem to bother anyone overmuch, the

defect never was rectified. I can remember racing about in the dinghy. Never on my own,

but it was still great sport. The dinghy was powered by a small Evinrude outboard; was

there any other kind in those days. That Evinrude came home to Garden City every year.

After decommissioning it spent the winter months in the garage. Every spring it was

cleaned up and lubricated then mounted on a 55 gallon steel drum filled with water. After

much cursing under his breath Pop would get the thing started, announce that it was fit

for another season, and off it would go to Shelter Island.

But back to racing

around in the dinghy. At least once a day we had to go ashore for groceries or some other

forgotten item. And then there were the obligatory late afternoon trips to the yacht club

for cocktails. Coca-cola for the kids of course. In between times someone would take us

out behind the Shelter Island Yacht Club where we would beach the dinghy. It was a

fascinating place back there. There were a few derelict and abandoned boats, a few others

being worked on, a number of small sailboats, and lots of discarded parts and boating

detritus to rummage through. As I look back, over the years and over the last sentence, I

realize from whence my son has acquired his scavenging instincts. Nothing remains from our

scavenging expeditions. Our mother probably reacted to the trash we picked up in much the

same way that I react to the collection of sticks, rubber bands and bits of plastic that

my son brings home.

Then there is learning

how to row the dinghy. You can't imagine the frustration of a small boy trying to please

his grandfather. In retrospect, I was far more impatient than he was. Not only did I want

to be done with life preservers, but I wanted to be allowed to go on a solo voyage with

the dinghy. These days I don't usually wear a life vest. I don't believe that the solo

dinghy voyage has ever come to pass: At one time I was too young, and now I am desirous of

companionship. To return to my story about rowing: My grandfather could row in the

conventional manner or with a single oar over the stern. When he realized that I didn't

have the coordination to work two oars so that I could go in a straight line he tried to

teach me how to scull. I didn't have the strength for that. He had to do the rowing. Now I

am strong enough to do the rowing but still have trouble going in a straight line while

being able to see only where I've been and not where I'm going.

The experience with the

dinghy was only surpassed by the opening and closing ride in the yacht club launch. The

launch driver seemed to have admirable, nearly unbelievable control and finesse, never

crunching the boats together as they heaved in different directions. While such control is

a learned skill, launch drivers, like truck drivers, are not considered skilled labor. And

this in spite of the fact that both are handling very expensive equipment and have our

lives in their hands. I wonder what will happen to their pay if the rule of comparable

worth ever becomes the law of the land.

Watching certain

competitive sports can be a real yawner. I include competitive golf, bowling and bicycle

racing in this category. The last of these I am qualified to comment on, but reserve that

for later in my narrative. Many would include sailboat racing in my list. Perhaps I have

been more selective in my watching, which means that for the most part I have let some

camera crew do the greater part of the watching in order to later indulge my vicarious

interests. On television I watched much of the re-taking of the America's Cup by Dennis

Conner and his crew off the coast of Australia. The film shown on TV was superbly edited.

It made one want to climb right on board and help grind the winches. Subsequent to

Conner's vindication I borrowed from a friend a commercially available VHS tape entitled

"Man Overboard!" The footage on this tape was filmed during one of the biennial

Bermuda's Cup races. In the scene from which the tape derives its name, one of the crew

members is swept overboard when he becomes entangled in a spinnaker sheet. In this scene

the crew losses control of the chute while trying to douse it. A puff, or should I say

gust, of wind catches the sail and whips the man overboard as quickly as one can wink an

eye. The fact that the man is rescued and later recovers fully makes this an exciting tape

without being ghoulish. All of this is by way of relating my rather meager recollections

of the first sailboat race I ever watched. Truth be told, I don't suppose I was really

watching the race any more than any one of us would sit on a street corner and watch the

light change. Rather, all of us on board Kay Ruth II were aware of the race being run on

the bay in front of the Shelter Island Yacht Club. The boats in this race were daysailers

with, I believe, very heavy fixed keels. The size and weight of the keel meant that if you

filled the boat with water you had better be sure that you knew how to swim. Needless to

say, the only reason that this episode sticks in my mind is that one of the boats did

capsize. There was some debate about how quickly the boat would sink. Miraculously the

kids got it upright again before it sank. I guess someone had been pulling my leg about

the thing being a real sinker. Oh, how I envied those kids who got to spend their summers

racing about the bay in a sailboat. To this day I can remember wondering why our family

couldn't have such a sailboat. I never voiced my sentiments though. By then I already was

aware of my parent's passion for tennis.

This next episode is

really fuzzy. You'll have to forgive me if, as a member of the cognoscenti, you realize

that the scene as I describe it could not have taken place on Shelter Island. Part of the

boating scene is that one fishes for dinner, either with a hook and line or by digging for

it in the mud flats. My Grandfather introduced me to both in the bay in front of the yacht

club. Of course, we didn't fish from his cabin cruiser. Using that piece of equipment to

go after flounder would be a bit of overkill. We took the dinghy out to a fishing hole,

baited our hooks and waited. In yesteryear, the days of plenty, we didn't have to wait for

long. My sense of time has probably been foreshortened by the intervening years, but Pop

isn't here to defend his virtue and patience so I'll stick to the days of plenty version.

My previous exposure to fish had been on the dinner plate on Fridays, ours being a

Catholic household. Catching a flounder, with a white underside and both eyes on the mud

colored topside was quite an experience. And cleaning it was something more. Particularly

when, as I've stated, my previous exposure to fish had been picking out the stray bone

while eating it. At that point I wasn't old enough to do more than observe, thank

goodness. Severed heads, entrails, and scales were a most unappetizing sight before

dinner. But the best part of the trip was catching the little sand sharks. From my

perspective they were real fighters. And the fact that Pop had to give them a swat on the

head with a hammer in order to subdue them to the point where he could get the hook out

made it all the more dramatic. Me, catching a shark, even if it was only a foot long!

(Years later, as a lifeguard, friends and I dumped an eight foot shark carcass in the

swimming pool. It created quite a stir when we took it out at the busiest time of day.)

Encouraged by our success with line and hook, Pop took us clamming the next day.

This was another dinghy

expedition. And I got to steer the boat with that old Evinrude spluttering away at the

stern. We had to go across the bay, dodging boats and mooring bouys, then under the

causeway into the tidal mudflats. We waded to about knee depth. Knee depth on a seven or

eight year old is pretty shallow water on everyone else. Nevertheless, you cannot see

bottom. To find the clams and scallops you wriggle and squish your feet down into the ooze

and mud until you find a hard object. Then, without moving your feet, you reach down and

pluck the little critter from that primordial muck. Slogging around in that stuff was all

right for a kid, but I doubt that I was very productive in finding our dinner. In any

case, we returned to the Kay Ruth about sunset, which meant we had to shuck the clams and

scallops by a very dim cabin light as we had no shore power, being on a mooring. I was

given a very dull knife in order to help with the job. Once again, I had seen this form of

wildlife on the dinner plate but had no idea of how it got from the bay onto the plate.

Some instructions on shucking were hastily given and I went to work on my first one. The

bivalves were in a pail of water so that they would open a little and so that they would

give up some of the sand and mud that they find so tasty. Parentherically, you should put

a bit of cornmeal in the water. Filter feeders will exchange their sand for the corn meal,

which is far less gritty when you get around to eating them. Anyway, I got my knife in,

then pried him open to the point where one could fit in a small finger. I'm not sure if I

put my finger in, or it just slipped into that scallop, but his reaction was immediate. I

hadn't severed the muscles it used for closing. I didn't know if scallops had teeth, but

my reflexes weren't going to wait long enough to find out. That poor scallop flew across

the cabin as I shook him off my finger, and I was in tears because one of those things had

bitten me. Furthermore, I was never going to eat another clam or scallop; I've since

broken that oath. Pop was not impressed by my demonstration of manhood. But he agreed to

prepare a different menu for me. That night I got beef and carrot stew for dinner. To this

day I swear that that was the best stew I have ever tasted. When my Mother reads this she

will probably insist that it was Dinty Moore from a can. So much for the discriminating

taste buds of youth.

In this last Shelter

Island episode we rented or borrowed a daysailer. Well, three of us did; my father, myself

and my sister. At the time my sister was about eight and had a cast on her arm, I was

about five. My brother would have been a year old so he could not accompany us. As

auxiliary power most daysailers are equipped with a paddle. This necessitates some pretty

fancy sailing when bringing the boat in at the end of the day. At the end of our voyage we

approached the dock in front of the Shelter Island Yacht Club, one adult and two very

small children. In this sort of manoeuvre one brings the boat around so that you head up

into the wind and stall right at dockside. The exercise is easier if you have someone in

the boat to grab the dock or hook a line on a piling to overcome any residual momentum.

Apparently we approached the dock with more than a little momentum. No, we didn't crash

into the dock and sink right there. But my Father did go to the bow to take hold of the

dock at the point where he thought the boat would stall. Unfortunately for him we were

still making a bit too much headway as we were passing parallel to the dock. Just as he

grabbed one of the pilings the wind shifted and gusted a bit. My Father was left hugging

the piling as my sister and I sailed away. All this in full view of the yacht club: My

Father gripping the piling in a bear hug, his feet scrambling for a barnacle of some size

two feet above water level , and a five and eight year old drifting out to sea. We have

all lived to tell the story.

At some point I

inherited a model sloop built by my father. He had built this boat at summer camp during

his youth. Length on the waterline was two feet. At least it seemed like two feet when I

was under five feet tall. But I suppose my current estimate of size is something like our

recollection of snowfall as youngsters. You know the sort of thing: "When I was a boy

we often had snowfalls that were half way up my thigh. Now it is never more than ankle

high". Ipso facto we conclude that the snow was never less than three feet deep when

we were kids. But to return to my story: This sloop was meant to be sailed short- handed;

or should I say no handed. As a consequence, while the jib was a masthead rig, it was less

than 100% of the foretriangle. Then there was the problem of steering the boat in the days

before remote radio control. This was solved with a very rudimentary auto helm. The auto

helm is, roughly speaking, a device that keeps the boat on the same tack, adjusting the

course of the boat as the wind backs and veers. In a full size boat one changes tack,

trims the sails, or changes course to adjust for changes in wind speed and direction. To

accomplish this the auto helm worked by stretching a rubber band between the mainsheet and

the tiller. With a puff of wind the rubber band would stretch, thereby giving a more

gentle tug on the tiller and causing the boat to fall off a bit. The effect of the rubber

band was to allow very short term sail trim while at the same time allowing the boat to

either fall off or head up. It still strikes me as very clever. The other marvel of this

boat was hull design. Remember that it was built in the early thirties. In order to

accomodate the woodworking skills of young hands the hull was carved from several blocks

of wood laminated together. But to reduce the amount of wood to be cut away she did not

have a full keel. Rather, the hull shape was more like today's full size racer-cruisers

with their fin keels. The keel was cut from heavy sheet metal and had ballast atteched to

the bottom edge, much like today's bulb keels. Lacking a full keel from which to hang the

traditional rudder, she was designed with a skeg rudder. So much for the innovations we

usually attribute to the America's Cup racers. When I inherited this boat she needed a bit

of refurbishing: She had been in my Grandmother's attic for thirty years. When I was done

we had sanded and varnished her spars, painted the hull below the water line green and the

topsides white, and sanded and varnished the mahogany deck. There was no cabin on this

sleek beauty. The sails were of cotton. Although they showed the water stains of previous

voyages, they didn't need to be replaced. We sailed her on the pond at Salisbury Park in

Nassau County. The park was about five miles from our house so I couldn't go there on my

own. But I do remember going with my Father and at least once with his Father. The major

concern was that the wind would die while the boat was in the middle of the pond. That

never did happen. The other concern was that she would collide with one of the other boats

on the pond, become entangled and be irretrievable. That never happened either. We did

have to race around the pond to retreive the boat at the end of each voyage. Without

shoreside control there was no way to get her to sail back to the point of origin. This

boat, handed down from father to son, spent most of its time in dry dock in my room. It

always gave me a thrill to see that boat over in the corner. Maybe someday I would own a

real boat just like her. I don't know what happened to that boat, but I wish had it now so

that I could pass it on to my son.

The town in which both I

and my parents grew up is a fairly prosperous and very stable community on Long Island.

The downside of this was that my siblings and I had teachers who had also had my parents

and aunts and uncles as students. The upside was that my parents knew some of the really

prosperous residents. In this socio-economic crowd there is always someone that owns a

sailboat. In our case the someone was Mr. Endeman, a boyhood chum of my Father's. Mr.

Endeman was a Wall Street lawyer. And we all know what that means. In any case, he was an

ardent sailor and owned a yawl, of about forty feet. Mr. Endeman's son, Freddy, was about

my age. In a bid to spend some quality time with their sons, and in the hope that the sons

would become friends, we all went sailing for a weekend. I am not sure if the boat was on

the South or North Shore of Long Island. It doesn't really matter. What mattered more was

that I was something of a midnight sailor. My Father gave me strict instructions about not

wetting the bed and assured me that he would get me up for a trip to the head in the

middle of the night. We left quite late on Friday afternoon and spent some time sailing

under the stars. I made it through that night all right. The next day was wonderful. It

was cool enough to require long pants and a sweater, but the wind was brisk and the

sailing fantastic. There is a photograph of me at the wheel, before the mizzenmast, but

for far less than two years. My father was mortified when, in spite of stern prior

warning, I did a bit of midnight sailing. But what did they expect after a day on the

water: The day's activity, the gentle motion of the boat and the sound of the water gently

caressing the hull just put me out stone cold. I never had a chance. At the time, Mr.

Endeman seemed to take it good naturedly, but we were never invited out again.

There is more to the

Endeman's yacht although it precedes my own ill-fated voyage. It was on the Endeman's boat

that my father and some of his friends sailed in the Bermuda Cup Race. This was something

that I was only vaguely aware of; kind of like being aware of the Tour de France. I

sometimes think that I spent my first twenty or so years in a shallow sleep, somewhat akin

to the nighttime torpor of the hummingbird but occasionally bordering on hibernation. My

Father's role as crew member is unclear at this point in time. It would be romantic to say

that he was the navigator. After all, he spent the greater part of World War II in

electronics school for the U.S. Navy. It is more likely that he was a slave on deck and in

the galley. They made it there and back, but I don't think any of them rushed out to sign

on for another try.

Fortunately, my yachting

adventures did not end with my ill- fated trip on the Endeman's yacht. During my Junior

High days I befriended one Tom Mulcahey. He had moved to Garden City to live with his aunt

and uncle, Edna and Fred. In private conversations we would refer to them as the Frednas.

Anyway, they had a power boat big enough for the four of us to go out for day trips on the

Great South Bay of Long Island. We would go fishing, clamming swimming and water skiing.

As usual, I was never really clear on where we were. If it had been up to me we never

would have gotten back to the slip in the afternoon. Every mudflat with grass on it looked

the same. Uncle Fred had spent so much time on the bay that he always knew where we were,

and best of all, knew the best fishing and clamming holes. By this time I had completely

recovered, or forgotten, my first experience with the retrieval and cleaning of shellfish.

These trips were great fun and only added fuel to the wistful daydreaming about my own

boat. I don't know that we ever really told the Frednas how much we appreciated them, and

I am sure that now it is too late.

While we're on the

subject of boats not driven by sail, let me recount my father's experience with a tramp

steamer. In relative terms, Garden City was untouched by the Great Depression. And as luck

would have it, the father of a chum of my father worked in the management of a steam ship

company. Dad and his friend lobbied hard to get permission to sail from New York, across

the Carribean and through the Panama Canal to California on one of the company's ships.

They would not sail as crew members. Neither of them was old enough to be employable and,

in those days, affluent youths were not going to be given papers by the appropriate union

for a summer's lark on a working freighter. With great anticipation they packed their

suitcases, being sure to include a good stock of books to read. As it turned out they were

the only passengers and had to rely on each other and their books for entertainment. They

had the luxury of dining at the captain's table. For the first few days it was pretty

heady stuff. But a healthy teenager can sit still in the confines of a freighter for only

so long. They asked the captain for a shipboard job so that they would not be quite so

bored. He refused, fearing that the unionized sailors would make his life difficult.

Teenagers can be pretty persistent, particularly given that at this point they were in the

Carribean. Now the sailing was not only boring but hot. It wasn't long before these callow

youths prevailed. At least they thought they had. The job given to them by the captain was

that of cleaning one of the heads. A job was a job. It was better than spending another

day sitting on deck reading and sweltering. Well, it might have been better were it not

for the fact that they were assigned the dirtiest head in the deepest, hottest part of the

hold. They did get the job done, but they kept to themselves for the rest of the voyage.

The moral for me was that going to sea could be great sport as long as sport was the

intent and there was someone else to clean the head.

Almost every middle

class kid goes to camp. My brother, sister and I were no exception. In the bad old days

they didn't have specialty sports or hobby camps. They were generally all purpose places

to park the kids for part of the summer. My brother and I went to Camp Sloane, in the

Berkshires. Special activities at general purpose camps usually cost extra and one must

register for them in advance. As it happened, I was registered for horseback riding,

several summers in a row, and my brother took sailing lessons. Presumably this decision

was made so that one of us would not be not in the other's shadow. I didn't mind the

choice: I liked horses, enough so that I spent a fair amount of free time mucking out

stalls and brushing the more even tempered horses. And the possibilities of owning a horse

or a sailboat were equally remote, so either choice was of little immediate or practical

value for anything but entertainment.

My sister Cathy's summer

camper experience was limited to Camp Blue Bay, where she did learn to sail. I was not

jealous. She is four years older than I am, and was five years ahead of me in school so

anything she did was so remote that it just wasn't relevant to my decision calculus.

Besides I did get some exposure to Blue Bay. At the end of the season it was opened to the

families of the Girl Scouts. We went there for a weekend trip. At the time I was having a

bout with either ring worm or impetigo and the salt water cured it, so I have a favorable

memory of the place. Perhaps there was a twinge of envy when Paul spent a summer washing

dishes at the same Camp. After all, there had to be Girl Scouts over the age of fifteen

that were needed to supervise all those little campers learning to sail and stay out of

the poison ivy.

This next story is not

one that I've dredged out of my memory banks but has something in common with one of the

previous episodes. To be perfectly honest I have absolutely no recollection of the

episode. One summer we rented a daysailer in Port Washington and sailed to City Island. At

one time City Island was a hotbed of boatbuilding activity and so was a popular

destination from ports along the North Shore. Upon our arrival there was apparently some

problem with keeping us kids under control while making fast to the dock. In the mayhem

Dad made a wild leap for the dock, being sure to step on a dock line that was laying

about. The rope rolled, his ankle went over with a sickening squelch. As luck would have

it he broke his ankle. He is in agony, but he is the skipper, and the boat must be

returned to Port Washington. To this day he has vivid memories of trying to hold the

icepack on his ankle while trying to skipper the boat. One would have thought that the

vision of clinging to the Shelter Island Yacht Club dock while his kids sailed off for

points unknown would have stifled the urge to make wild leaps. We didn't rent a boat again

until much later; like thirty years later.

At the beginning of the 1980's I worked at the

Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin. Life in a walled and isolated city is another

story. Two of my colleagues kept boats on the Wannsee, which is a huge lake on the

southwest side of the city. Joachim's boat, pictured at left, was about 28 feet of

classic wooden sloop. Mannfred's boat was about the same size, but of modern

fiberglass construction. Yes, it surprised me too that there were so many good sized

boats on a lake in a city to which access was strictly controlled by a foreign power.

And yes, there were certain parts of the lake that were off-limits. One

risked bringing down the wrath of the East German border guards if you tried to visit the

wrong parts of the lake. Anyway, sailing in Berlin was a gas.

At the beginning of the 1980's I worked at the

Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin. Life in a walled and isolated city is another

story. Two of my colleagues kept boats on the Wannsee, which is a huge lake on the

southwest side of the city. Joachim's boat, pictured at left, was about 28 feet of

classic wooden sloop. Mannfred's boat was about the same size, but of modern

fiberglass construction. Yes, it surprised me too that there were so many good sized

boats on a lake in a city to which access was strictly controlled by a foreign power.

And yes, there were certain parts of the lake that were off-limits. One

risked bringing down the wrath of the East German border guards if you tried to visit the

wrong parts of the lake. Anyway, sailing in Berlin was a gas.

To celebrate one of my

parent's wedding annivarsaries, at their expense, we rented a house on the Connecticut

side of the Sound, not far from Mystic Seaport. We rented a sloop for a little day sail.

This was our first rental since the City Island episode thirty years earlier. Everything

went more smoothly this time, there were no wild grabs for or leaps to the dock and it

proved to be very relaxing. Encouraged by this, Paul, Cathy and my father rented a Hobie

Cat several days later. These boats can really scream when they are not trying to sail

into the wind. The three of them had a great time on their afternoon sail. As all good

sailors know, when the weather is stable the wind often dies in the late afternoon.

Apparently they had forgotten this. The wind did die. The sun was setting. They were quite

far from the shore. And they didn't have a paddle. They took turns swimming the boat

toward shore. The fleet owner noticed their distress and went out with his power launch to

bring them in to shore. He must have been afraid that he would miss dinner if he waited

for them to swim to shore and wasn't too concerned about bruising their egos. I am glad I

wasn't in on that little fiasco.

While enjoying this

summer idyll on the Connecticut shore we made a family visit to Mystic Seaport. A visit to

Mystic always makes the salt in your veins run a little faster. The Seaport is a restored

whaling village. The idea is very much like the Rockefeller endowed effort at

Williamsburg, Virginia. Part of the ambiance of the place is achieved with the strategic

placement of ships' anchors on the grounds. We had made a trip there as a family when we

were kids. There is a picture of Paul and I, both under ten years of age, perched on the

flukes of one of those anchors. On this return trip we had my son Christopher, then two,

with us. We managed to find the anchor used for the earlier pose and have added a picture

of Paul and Christopher to the family album. Talk about nostalgia.

Well, now we are getting

up to the present day. And we can begin talking about serious envy, bordering on jealousy.

Several years ago Paul began to talk about buying a big enough boat to live on, i.e., it

would be his principal domicile. He even got to the point where he was doing some serious

research about the possibility. The principle sticking point was money. Banks regularly

loan money, in the form of a mortgage, for the purchase of a boat. But in the northeast

such lending is for the purchase of a boat as a recreational purchase, not as a residence.

The idea of lending money to buy a boat and live on it year around was alien to them. At

the time Paul had a friend who was actually doing it, living on board. Beyond that, Paul

was young, white and free. He might just have pulled it off if he had worked on it a bit

longer. His middle class, common sense upbringing prevailed, and when he met the woman of

his dreams he eschewed the boat. Instead he got married and bought a condo. I think our

parents were relieved that he stopped dreaming before he could indulge in such a

wild-assed, irresponsible notion as living on a boat, in northern climes at that.

So, you ask, why take

the plunge into sailing? Aren't there other sports one can pursue? After all, as part of a

two career, one child family I meet the definition of a yuppie. And, to continue the line

of reasoning, the yuppie sports are running, tennis and triathlons.

The truth is that

triathletes are missing a few marbles and running is a bore. That leaves tennis. You may

recall that I mentioned in passing that my parents were avid tennis players. At age 65 my

father still was. Not only avid, but good. At my best I had to struggle to beat my mother;

and I never could beat my father. More by accident than by design I started bicycle racing

as a graduate student. Over the ensuing ten years it became more and more consuming,

requiring an ever greater commitment. That is not to suggest that it did not have its

rewards. One year I did win gold and silver medals at the national championships for 'old

men and relics'. Nonetheless, the cost of achieving anything was great. My wife barely

tolerated my involvement, and it was not something that my son could be involved in for a

number of years. Training for aerobic sports is time consuming, particularly when your

goal is to be a gold medalist. Eventually I found that the time spent training was causing

me to depreciate the stock of human capital I had built up as a graduate student, at the

expense of my career. Add to that the gross mismanagement of the amateur side of the sport

at all levels and you have one frustrated bike rider. Finally, I decided that I had had it

with competitive sport. In the middle of a District Championship race and in a position to

qualify for the National Championships, which are used to select National and Olympic

teams, I rode off the track for the last time. I didn't like its management, I didn't like

what it took to win and to then market the accomplishment. And most of all, I was afraid

of what it might someday cost my family.

With the exception of a

few years I have always lived fairly near the water. I have always been fascinated by, and

at times dreamed of owning, a sailboat. Here was something we could do as a family. Unlike

jogging or cycling, the stronger members of the family don't have to wait for the others.

Differences in skill and knowledge are not so readily apparent. And sailing can be about

the most relaxing non-competitive sport one could ever endeavor to find.

On Board Boats: Table of

Contents

Comments or Correspondence

eastern tip of Long Island, New York. After a stint in college in

Philadelphia and commissions in both the Army and the Navy he did return to Shelter

Island, albeit for short stays in the summer. My mother and grandmother often talk of

spending summers in a rented house on Shelter Island. As a Naval Reserve Officer and a

native of an island with a long seafaring history it wasn't long before my grandfather

owned a boat. In fact, there were at least two. To the above right is the first Kay

Ruth. This photo was taken in 1946.

eastern tip of Long Island, New York. After a stint in college in

Philadelphia and commissions in both the Army and the Navy he did return to Shelter

Island, albeit for short stays in the summer. My mother and grandmother often talk of

spending summers in a rented house on Shelter Island. As a Naval Reserve Officer and a

native of an island with a long seafaring history it wasn't long before my grandfather

owned a boat. In fact, there were at least two. To the above right is the first Kay

Ruth. This photo was taken in 1946. The only one of these boats

with which I was familiar was the Kay Ruth II, named after my mother and

grandmother. The Kay Ruth II is pictured at the left. My grandfather owned her

from 1952-1963. The boat was a forty foot Matthews outfitted as a sport fisher, with two

great long outriggers originating at the aft edge of the cabin and rising into the

sky. In the photo they are in front of the cabin so my grandfather must have changed

them at some point. Those outriggers gave the impression of being the antennae of a

gigantic bug. But the clear plastic rings to guide the fishing lines along their length,

and the intermittent black stripes along their white length, gave the lie to that

interpretation. She had twin inboard engines, a v-berth in the forecastle, an owner's

cabin, galley, head, and large saloon. The dining table and opposing benches could be

folded down to form a double bed. The banquette, also in the saloon, provided

accommodation for at least one more tired sailor. The hull and cabin were, of course,

wood. Fiberglass was not then an accepted construction material. The quantity of high

gloss mahogany was beyond belief. Every winter the boat was taken out of the water and

kept under cover so that all that wood could be repainted and varnished. All in all, it

was quite a boat, at least in the eyes of a boy less than ten years old.

The only one of these boats

with which I was familiar was the Kay Ruth II, named after my mother and

grandmother. The Kay Ruth II is pictured at the left. My grandfather owned her

from 1952-1963. The boat was a forty foot Matthews outfitted as a sport fisher, with two

great long outriggers originating at the aft edge of the cabin and rising into the

sky. In the photo they are in front of the cabin so my grandfather must have changed

them at some point. Those outriggers gave the impression of being the antennae of a

gigantic bug. But the clear plastic rings to guide the fishing lines along their length,

and the intermittent black stripes along their white length, gave the lie to that

interpretation. She had twin inboard engines, a v-berth in the forecastle, an owner's

cabin, galley, head, and large saloon. The dining table and opposing benches could be

folded down to form a double bed. The banquette, also in the saloon, provided

accommodation for at least one more tired sailor. The hull and cabin were, of course,

wood. Fiberglass was not then an accepted construction material. The quantity of high

gloss mahogany was beyond belief. Every winter the boat was taken out of the water and

kept under cover so that all that wood could be repainted and varnished. All in all, it

was quite a boat, at least in the eyes of a boy less than ten years old. To

the left is a clipping my grandmother sent to me. It describes one of my

grandfather's voyages with Kay Ruth II. It must have been in 1952 or 1953, given the

discussion in the first paragraph and the period during which he owned the boat.

To

the left is a clipping my grandmother sent to me. It describes one of my

grandfather's voyages with Kay Ruth II. It must have been in 1952 or 1953, given the

discussion in the first paragraph and the period during which he owned the boat. At the beginning of the 1980's I worked at the

Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin. Life in a walled and isolated city is another

story. Two of my colleagues kept boats on the Wannsee, which is a huge lake on the

southwest side of the city. Joachim's boat, pictured at left, was about 28 feet of

classic wooden sloop. Mannfred's boat was about the same size, but of modern

fiberglass construction. Yes, it surprised me too that there were so many good sized

boats on a lake in a city to which access was strictly controlled by a foreign power.

And yes, there were certain parts of the lake that were off-limits. One

risked bringing down the wrath of the East German border guards if you tried to visit the

wrong parts of the lake. Anyway, sailing in Berlin was a gas.

At the beginning of the 1980's I worked at the

Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin. Life in a walled and isolated city is another

story. Two of my colleagues kept boats on the Wannsee, which is a huge lake on the

southwest side of the city. Joachim's boat, pictured at left, was about 28 feet of

classic wooden sloop. Mannfred's boat was about the same size, but of modern

fiberglass construction. Yes, it surprised me too that there were so many good sized

boats on a lake in a city to which access was strictly controlled by a foreign power.

And yes, there were certain parts of the lake that were off-limits. One

risked bringing down the wrath of the East German border guards if you tried to visit the

wrong parts of the lake. Anyway, sailing in Berlin was a gas.