The New York Times

November 3, 1998

Gates on Tape: Scant Memory of Key Details

By STEVE LOHR and JOEL BRINKLEY

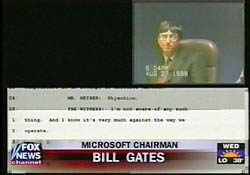

WASHINGTON -- The Bill Gates on the courtroom screen was evasive and uninformed, pedantic and taciturn -- a world apart from his reputation as a brilliant business strategist, guiding every step in Microsoft Corp.'s rise to dominance in computing.

Fox NewsThe posture varied as Microsoft's chairman, William H. Gates, was videotaped while responding to the Government's questions in August. In two hours of videotaped questioning shown at the Microsoft antitrust trial here Monday, a small part of the three-day deposition he gave last summer, Gates professed ignorance of several key charges in the government's case including allegations that he was involved in plans to bully competitors like Apple Computer Inc. and Netscape Communications Corp. to step back from Internet software markets that Microsoft sought to dominate.

When presented with e-mail messages he had written, he often said he did not recognize the messages or recall the discussions surrounding them.

To question after question he answered, "I don't remember using those words," or "I'm not sure what you're trying to say.".

In some cases Gates' answers were so banal that even Thomas Penfield Jackson, the U.S. District Court judge who is hearing the the case, chuckled and shook his head. Asked once, "who was at the executive staff meeting" where a key discussion took place, Gates said simply: "Probably members of the executive staff."

Microsoft replies that the few hours of taped excerpts, drawn from 20 hours of questioning by government lawyers, were often taken out of context, selected merely to embarrass Gates and Microsoft with little direct bearing on the case. Gates, Microsoft says, was obviously not going to cooperate with prosecutors trying to put words in his mouth.

For the most part, both Gates, the nation's wealthiest man, and his questioner, David Boies, the Justice Department's trial lawyer, remained civil and polite. Boies, however, did show a flash or two of irritation at Gates' plodding evasions -- so at odds with his public image as a quick-witted tactician, immersed in every significant detail of Microsoft's business. At times, Boies pointedly reminded Gates that he was under oath.

The pile of e-mail offered as evidence Monday vividly showed the round-the-clock pace at Microsoft, a pace set by Gates. E-mail messages sent to him at 4 a.m. were answered a few hours later.

Still, through two hours of verbal thrusts and parries, Boies never quite succeeded in trapping Gates, and Gates was generally unable to discredit Boies' assertions.

Gates, dressed in a hunter green suit with a brown striped tie, sitting at a plain conference table at Microsoft's headquarters next to his attorney, seldom smiled but never raised his voice.

TODAY'S TRIAL COVERAGE

Taking in the (Web) Site of This Virtual Defense

An Internal Memo Shows Microsoft Executives' Concern Over Free Software

Long pauses -- some more than 20 second long -- hung between many of Boies' questions and Gates' answers. Microsoft's chairman seldom looked his questioner in the eye, gazing down at the table instead. As he read documents that were handed to him, sometimes, he rocked back and forth in his chair.

For the last week, the government has been trying to play the Gates deposition in court, but Microsoft's drawn-out cross examination of government witnesses by Microsoft's trial lawyer, Jack Warden, had left no time. The announcement that it would be played Monday came as a surprise.

During the deposition, taped over three days in August, Gates was confronted again and again by e-mail -- his own, and messages sent to him by other Microsoft executives.

The government's case, in its broadest terms, is that Microsoft has used its market muscle to fashion a network of relationships that would insure that the rise of the Internet did not weaken its dominance. It began with trying, in a meeting that took place on June 21, 1995, to divide up with its main rival, Netscape Communications Corp., the market for software used to browse the World Wide Web.

In his deposition, Gates said that during the period around June 1995 he had "no sense of what Netscape was doing."

Microsoft documents often seem to contradict Gates' profession of ignorance. In an internal document titled "The Internet Tidal Wave," written on May 26, 1995, by Gates himself, he gives an authoritative analysis of Netscape's strategy. He called Netscape a "new competitor 'born' on the Internet," whose goal was to "commoditize" the value of the personal computer operating system.

The government asserts that Microsoft unfairly used its market muscle to force Apple to choose its Internet Explorer instead of Netscape's Navigator as the main browser on Apple Macintosh computers. A key weapon in that campaign, the government says, was to threaten to cancel developing the Macintosh version of its industry-standard Microsoft Office software. This threat, Gates was informed in an e-mail from a subordinate "is certainly the strongest bargaining point we have, as doing so will do a great deal of harm to Apple immediately."

On June 23, 1996, Gates sent an e-mail to two of his senior aides, Paul Maritz and Brad Silverberg, that said one of his "two key goals" in Microsoft's relationship with Apple was to "get them to embrace Internet Explorer in some way."

In August 1997, Microsoft and Apple did announce a deal in which Apple agreed to make Internet Explorer the default browser on its Macintosh machines. But Microsoft says that the government is presenting a skewed portrait of the deal, which included a $150 million investment in Apple and a separate payment estimated at $100 million.

The main element in the deal, Microsoft says, was settling a long-running patent dispute in which Apple had demanded first $1.2 billion and then "several hundred million dollars" at two points in 1997, accusing Microsoft of stealing its intellectual property.

At another point in the testimony, Boies, the Justice Department's trial lawyer, brought up Sun Microsystems. He asked Gates if he had tried to "get Apple to agree to help you to undermine Sun?" He showed Gates an e-mail written on Aug. 8, 1997, sent to Maritz and others. In dealing with Apple, Gates wants to get "as much mileage as possible" in competing against other Internet software companies. "In other words," he writes, "a real advantage against Sun and Netscape."

He concludes the e-mail by asking his aides, "Do we have a clear plan on what we want Apple to do to undermine Sun?"

Boies then asked Gates what he meant when he asked that question. Pausing and staring down at his own brief message, Gates eventually replied, "I don't know."

The government is alleging that Microsoft has repeatedly used its market power for anticompetitive ends, prodding partners and competitors to divide, or stay out of, markets that Microsoft wants to dominate.

When asked about these allegations in general, Gates gave his most unequivocal reply. "Are you aware," Boies asked, "of any instances in which representatives of Microsoft have met with competitors in an attempt to allocate markets?"

Gates replied, "I'm not aware of any such thing. And I know it's very much against the way we operate."

Boies probed further to ask, "It would be against company policy to do that."

And Gates answered, "That's right."