McALLEN,

Texas -- For Victor Jaramillo and his family, NAFTA has been a gateway to the American

dream.

McALLEN,

Texas -- For Victor Jaramillo and his family, NAFTA has been a gateway to the American

dream.The Philadelphia Inquirer

January 1, 1999

TRADE

McALLEN,

Texas -- For Victor Jaramillo and his family, NAFTA has been a gateway to the American

dream.

McALLEN,

Texas -- For Victor Jaramillo and his family, NAFTA has been a gateway to the American

dream.

For Teodoro Guido, the treaty has become a Mexican nightmare.

The North American Free Trade Agreement helped Jaramillo, a Mexican native, start his own business in the United States. His Red & Hot Produce, based in this border town, is an importer and distributor of dried hot pepper and other crops grown in his home state of Zacatecas in central Mexico.

"The mentality is different here because only good merchandise sells," he said. "In Mexico, you can sell whether your product is good or bad."

But Guido, a pig farmer from Guanajuato, another central Mexican state, has struggled to compete with cheaper U.S. imports. He blames the free trade accord for driving many of the farmers in his hometown of Iramuco out of business.

Five years after the North American Free Trade Agreement started tearing down trade barriers in the United States, Mexico and Canada, the treaty still is controversial for many businesses and individuals.

Take the apparel industry.

Patricia Guzman Ramos, 18, starts her workday in Emiliano Zapata, Mexico, doing aerobics with fellow workers, then perches on an ergonomic chair, under soft light, in well-chilled air, and sews for nine hours. Her first job seems as far from the common picture of a sweatshop as can be. And that's exactly the image desired by the American apparel companies that have hired her to work for about $3.25 a day under NAFTA.

Indeed, the 13 apparel factories in various stages of operation and construction on the outskirts of this small town 62 miles south of Mexico City are supposed to represent a new, kinder face for NAFTA, which turns five today..

But to the U.S. apparel unions whose ranks have been decimated since the treaty took effect, Guzman's work represents just what they fear: Good jobs being exported.

"It's a flood," said Mark Levinson, chief economist of the Union of Needle Trades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE), the largest U.S. apparel-related trade union. "In the U.S., there's this concern about Asian steel flooding domestic steel. Our equivalent is Mexican apparel. It's kind of unprecedented."

Since NAFTA was signed, Mexico has become the top exporter of apparel into the United States, adding the "Hecho en Mexico" (Made in Mexico) logo to labels ranging from The Gap to DKNY and Liz Claiborne. The apparel sector's contribution to Mexico's gross domestic product has grown 250 percent, making it one of the engines of Mexico's stellar growth in manufacturing in the NAFTA era.

That growth has greatly benefited the moribund U.S. textile industry, which is trading heavily with Mexico, where the new North American shirt or skirt is made with U.S. yarn and fabric.

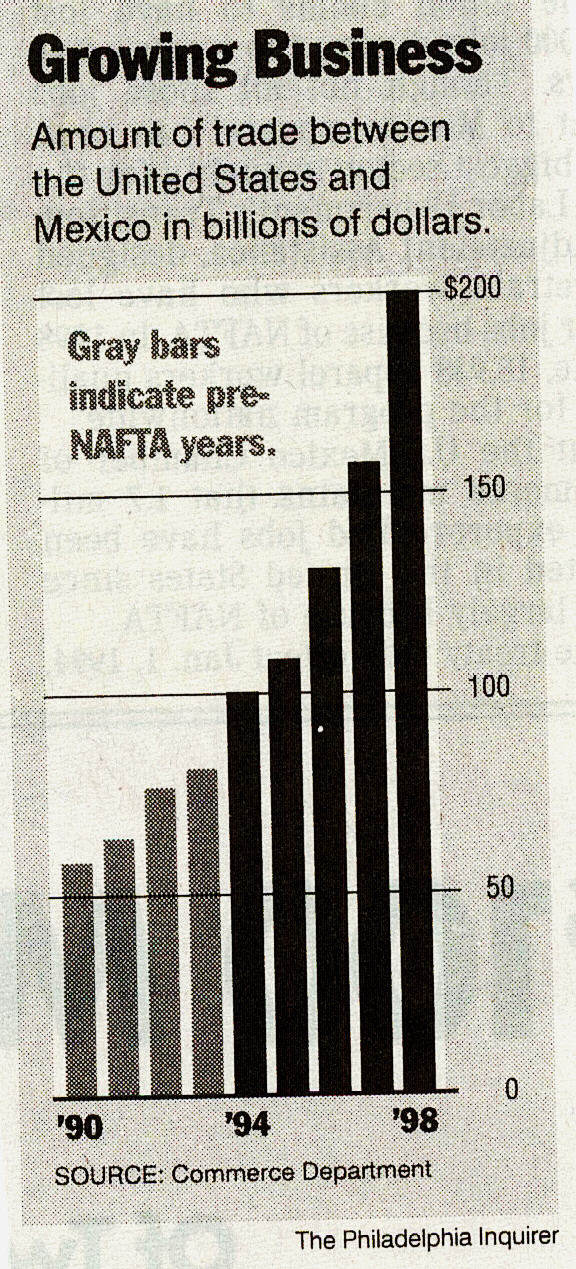

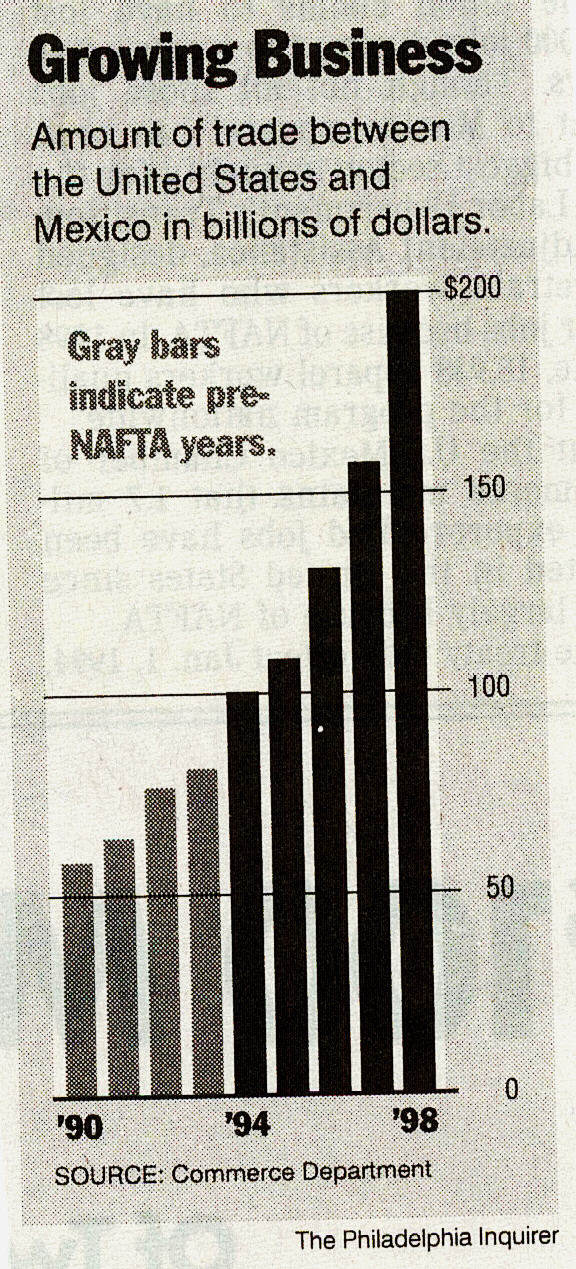

Similar transborder links are apparent in an array of industries, from automobiles to electronics to pharmaceuticals, which have helped push overall trade between Mexico and the United States from about $81 billion a year pre-NAFTA to an estimated $200 billion this year. Both Mexico and the United States brag that trade-related employment is up significantly as a result, as is virtually every other indicator that counts.

Yet few people on either side of the border seem eager to toast NAFTA.

"I don't think we've done our job," U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Jeffrey Davidow acknowledged recently. "I don't think we have conveyed to the American people the value of free trade with Mexico."

NAFTA's enemies, primarily unions, have kept up the struggle against the pact. In 1997, they helped beat back a proposal to allow President Clinton "fast-track" authority to replicate NAFTA with other Latin American nations from Guatemala to Chile. They did it by posing a simple question: "If you like NAFTA, then vote for fast track." Congress failed to pass the measure.

"All the promises made on NAFTA's behalf have not come true," said UNITE's Levinson. "NAFTA was sold in the United States as: Yes, some investment would be diverted from the U.S. and Canada, but NAFTA was going to lead to the creation of a middle class in Mexico, and Mexico would have such a rising middle class it would be able to buy more goods and so it would be a net plus.

"They also said maquiladoras [ duty-free assembly plants ] would decline with the rise of an internal market," he said. "Every single one of those promises made by NAFTA has not happened."

The union claims to have lost 300,000 jobs during the treaty's five years. Though not

all those jobs went to Mexico, apparel has been the biggest sector to qualify for the U.S.

Labor Department's Transitional Adjustment Assistance, designed to retrain workers who

have lost their jobs because of NAFTA. In 1998 alone, 18,938 apparel workers qualified for

the program nationwide.

But the U.S.-Mexico Chamber of Commerce maintains that 1.7 million export-related jobs

have been created in the United States since 1993 largely because of NAFTA.

The treaty took effect Jan. 1, 1994, linking more than 360 million consumers in a $6 trillion market. Over 15 years, it is to gradually eliminate all trade barriers between the three nations.

NAFTA included side agreements intended to protect the environment and labor rights. It also gave Mexicans new opportunities to work in the United States,

Jaramillo, the hot-pepper importer, became eligible under NAFTA for a U.S. trader/investor visa to open his own business two years ago in McAllen.

For years he had made little money trying to sell his peppers in Mexico City. Then he found out about the McAllen Produce Terminal Market, a project just 3 miles north of the border designed to help Mexican farmers become their own U.S. distributors.

Now he is enjoying a middle-class life in the United States and the chance to give his two children a better future.

"They will have more opportunities for all kinds of things; it's going to be a great advantage for them," he said. "Education is better here, and they will not have to worry about economic turmoil in Mexico."

But residents of Iramuco, Guido's home town, also are heading north of the border -- but under different circumstances.

"People are desperate because now there's no way to make a living," he said.

Small farmers say they have a tough time competing against U.S. farm imports because American producers tend to be much larger and more efficient, helping keep prices lower. Mexican farmers also have a hard time getting loans, now carrying high interest rates.

While Guido has chosen to stay in Iramuco, he estimates that about a third of the 15,000 residents have opted to cross the border as undocumented aliens.

As a result, a bus from the tiny town makes daily, 16-hour trips directly to the border town of Nuevo Laredo, across from Laredo, Texas.

But on the U.S. side of the border, unions say jobs have been heading south. Companies that have moved operations to Mexico since NAFTA include Zenith Electronics Corp., Nintendo of America, Mattel, Sara Lee Knit Products, Vanity Fair Mills, and Pendleton Woolen Mills.

General Motors and other companies that had operations in Mexico before 1994 have gradually moved more of their production to Mexican plants. They insist the moves were made independently of NAFTA.

One lure is the lower cost of labor. While the wages for production workers in the United States have grown steadily, those of Mexican workers have fallen, after adjustment for inflation, since the 1995 economic crisis. Mexico's minimum wage is $3.40 a day. The minimum wage in the United States is, in comparison, $5.15 an hour.

NAFTA advocates say the treaty did not cause the jobs to leave the country. They say companies looking for lower wages can just as easily take their plants to such other low-wage countries as China, India, or the Dominican Republic.

"What is affecting American workers is the process of globalization," Davidow, the U.S. ambassador, said.

Unions reject that argument. "There is no way to know where companies would have gone in the absence of NAFTA," Thea Lee, spokeswoman for the AFL-CIO in Washington, said.

© 1998 Philadelphia Newspapers Inc.

Return to Econ 52 Syllabus |

Return to Econ 92 Syllabus | Return to Econ 51 Syllabus |